Wind Chill vs. True Cryotherapy: Why Feeling Colder Isn’t the Same as Getting Colder

- CryoBuilt

- Jan 3

- 5 min read

If you’ve ever looked at your weather app and seen 25°F with a “feels like” temperature of 15°F, you’ve encountered wind chill.

That “feels like” number often gets confused with actual temperature—and in the world of cryotherapy, that confusion matters. Wind chill plays a role in how cold something feels, but it does not change the true temperature of the environment. Understanding that difference is key to understanding how real cryotherapy works.

At CryoBuilt, wind chill is used intentionally as a supporting mechanism, not as the source of cold itself. And that distinction is exactly where many cold-based modalities diverge.

What Wind Chill Actually Is

Wind chill is a calculation that describes how quickly heat is removed from your skin when air is moving across it. Your body is surrounded by a thin layer of warm air that acts as insulation. When wind disrupts that layer, heat escapes faster, making you feel colder than the actual air temperature.

A simple analogy is blowing on hot soup. The soup doesn’t instantly become colder in temperature, but the surface cools faster because moving air accelerates heat loss. That’s wind chill.

Importantly, wind chill does not lower air temperature. It only increases convective heat loss at the skin’s surface. The air itself remains exactly the same temperature.

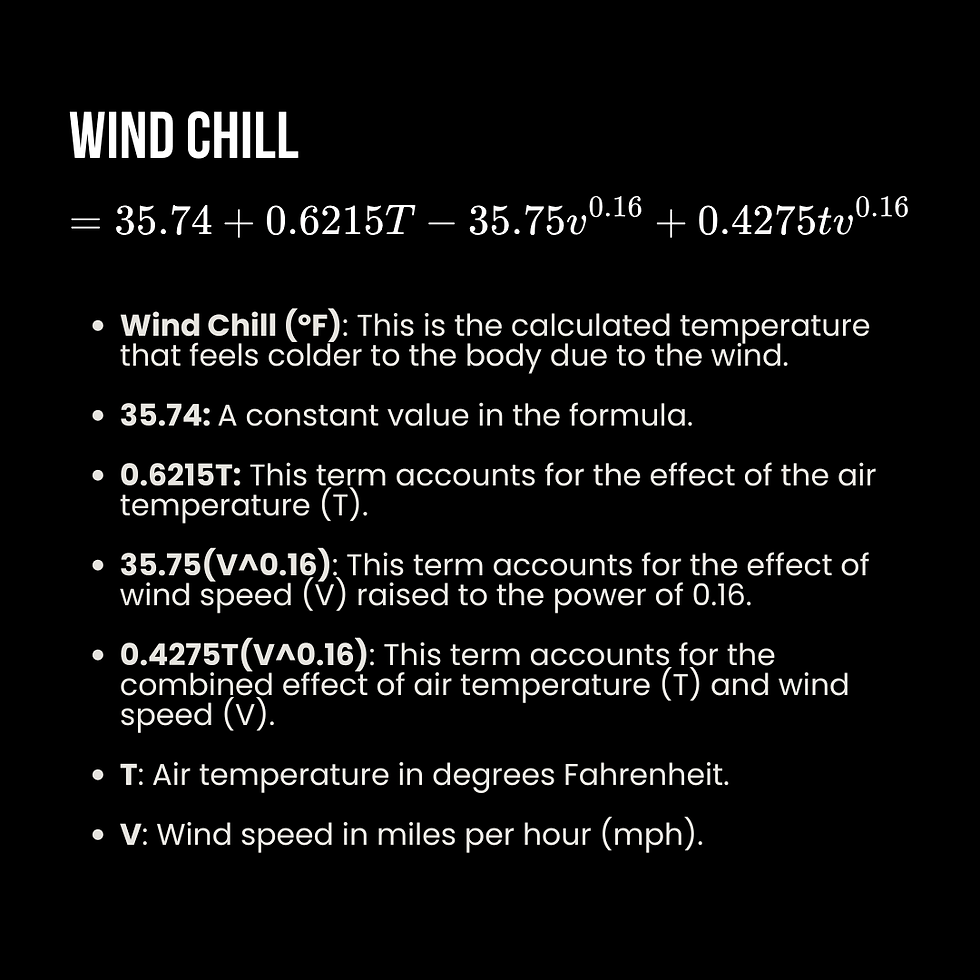

How Wind Chill Is Calculated

Meteorologists calculate wind chill using a standardized equation that estimates how quickly heat is removed from exposed skin based on two variables: air temperature and wind speed. The result is a wind chill temperature, which represents how cold the environment feels due to accelerated heat loss, not how cold the air actually is.

In simplified terms, the calculation assumes a constant skin temperature and models how moving air increases convective heat transfer away from the body. As wind speed rises, heat is pulled away from the skin faster, lowering the “feels like” temperature even though the air itself remains unchanged.

The modern wind chill formula includes:

A constant baseline value

A temperature component that reflects ambient air temperature

A wind speed component raised to a fractional power

A combined term that accounts for how temperature and wind interact

What matters most is this: wind chill only describes the rate of surface heat loss. It does not measure internal cooling, tissue temperature change, or physiological response. It also has a ceiling. Once heat is being removed from the skin as fast as possible, increasing wind speed further does not meaningfully increase cooling—it simply increases discomfort and risk.

This is why wind chill is useful for weather warnings and exposure safety—but insufficient on its own to explain or deliver true cryotherapy outcomes.

Why Wind Chill Has Limits

Wind chill is not infinite. Once heat is being removed from the skin as fast as physics allows, adding more wind doesn’t make the body meaningfully colder. Instead, it increases discomfort and risk.

In outdoor environments, extreme wind chill can accelerate frostbite. In controlled environments like cryotherapy chambers, excessive airflow can become counterproductive, stripping surface heat too aggressively without improving physiological outcomes.

This is where precision matters.

How Electric Cryotherapy Actually Works

Electric cryotherapy does not rely on wind to create cold.

CryoBuilt chambers use industrial electric refrigeration systems to lower the actual air temperature inside the chamber to true cryogenic levels—typically around –166°F (–110°C) and below. This extreme temperature is stable, measurable, and consistent across sessions.

The physiological effects of cryotherapy are driven by the temperature differential between the body and its environment. When skin at approximately 90°F is suddenly exposed to air at –166°F or colder, the body responds immediately.

Blood vessels constrict rapidly. Skin temperature drops 30–40°F within minutes. Norepinephrine spikes dramatically, often reaching several times baseline levels. These responses are not driven by sensation or perceived cold. They are driven by actual temperature.

Without reaching true cryogenic temperatures, these responses simply do not occur at the same magnitude.

Where Wind Chill Fits Into Cryotherapy

In CryoBuilt systems, airflow is carefully controlled—not maximized.

Air movement serves one primary function: efficient distribution of already-cold air across the skin. Moderate airflow helps eliminate warm pockets, ensures even exposure, and improves consistency from session to session.

CryoBuilt chambers offer multiple airflow levels so users can match the experience to their tolerance and goals. At lower airflow settings, the cold feels smoother and more approachable. At higher settings, surface cooling happens faster and the experience feels more intense.

What airflow does not do is replace temperature.

Wind chill can increase perceived cold and speed up surface heat loss, but it cannot create the deep thermal stress required for true cryotherapy. You cannot compensate for insufficient temperature with more wind.

Why “Feeling Colder” Isn’t the Goal

One of the most common misconceptions in cold exposure is equating discomfort with effectiveness.

Wind can make an environment feel brutally cold, even at relatively mild temperatures. But feeling cold does not guarantee vasoconstriction, hormonal response, or recovery signaling. Those outcomes depend on how cold the environment actually is—not how aggressive it feels.

At temperatures like –50°F or –60°F, even with strong airflow, skin cools more slowly, vasoconstriction is limited, and norepinephrine response is muted. The body simply does not interpret the stimulus the same way it does at –166°F and below.

This is why CryoBuilt prioritizes temperature first, then uses airflow as a refinement tool rather than a primary driver.

Wind Chill as a Value-Add, Not a Standalone Solution

When used correctly, wind chill enhances cryotherapy. It improves air circulation, creates more uniform exposure, and helps fine-tune the experience for different users.

When used incorrectly—as a substitute for temperature—it becomes a shortcut that delivers sensation without substance.

True cryotherapy is not about how cold it feels in the moment. It’s about triggering a specific, measurable physiological response that only occurs at extreme temperatures.

Wind chill can support that process. It cannot replace it.

The Bottom Line

Wind chill describes how cold it feels when moving air accelerates heat loss from the skin. It does not change air temperature, and it does not create the biological conditions required for true cryotherapy.

Electric cryotherapy works because it delivers actual cryogenic temperatures, creating a massive thermal gradient that drives vasoconstriction, hormonal response, and recovery signaling.

At CryoBuilt, airflow is engineered as a precision tool—one that enhances an already powerful stimulus rather than attempting to manufacture cold through force.

Because in cryotherapy, the driver of results isn’t sensation.

It’s temperature.

References

Thompson, Elizabeth. 2024. What Is Wind Chill? Popular Science, January 16.https://www.popsci.com/science/what-is-wind-chill/

Louis, J., Theurot, D., Filliard, J. R., Volondat, M., Dugué, B., & Dupuy, O. 2020. The use of whole-body cryotherapy: time- and dose-response investigation on circulating blood catecholamines and heart rate variability. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 120(8), 1733–1743.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04406-5

Costello, J. T., Culligan, K., Selfe, J., & Donnelly, A. E. 2012. Muscle, skin and core temperature after −110°C cold air and 8°C water treatment. PLOS ONE, 7(11), e48190.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048190

Rose, C. L., McGuire, H., Graham, K., Siegler, J., de St Groth, B. F., Caillaud, C., & Edwards, K. M. 2023. Partial body cryotherapy exposure drives acute redistribution of circulating lymphocytes: preliminary findings. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 123(2), 407–415.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-022-05058-3

Comments